The Walrus Talks Inclusion: Tatiana Zakharova on the Magic of Play

Earthscape’s Tatiana Zakharova was recently a presenter at “The Walrus Talks Inclusion” event in Waterloo on October 23, 2019. This post is adapted from her presentation. You can also view the lecture in its entirety on YouTube here.

Tatiana was one of seven speakers invited to participate. They each addressed the topic: “How design, technology, education and more can remove barriers for people with disabilities.”

Playground Inclusivity

Accessibility and inclusivity truly are topics we think about when designing every single playground project. Though we certainly don’t have all the answers, we do have some ideas to share.

First, I want to talk about the concept of “universal design.” Whether it is defined as including everyone or the widest possible audience, universal design is a lovely phrase, but an impossible concept. The problem with its implementation is that it is reductionist. It takes this big messy idea of “inclusivity” and cuts it into small, graspable portions like “simple to use”, “intuitive”, or “requiring low physical effort.”

But our abilities and desires are uniquely situated in our different realities. So, I cannot believe in a positivist term like “universal” when that implies that having one single approach to physical reality can meet all needs. This is NOT a statement of defeat. Instead, I think the entire process of good design is a process of working on inclusion. Inclusion is a living concept – and design has a similar iterative quality.

Playground design must always meet safety and accessibility standards because that is the law. But, in every project, we also consider different ways to play, and how that impacts inclusivity.

Theories of gender predict different play behaviours between boys and girls. Research shows that, overall, girls tend to be less physically active and prefer different activities: creating, imaginative play, climbing, sitting. So what can we do to ensure there are different play opportunities to appeal to more children? To answer this question, let me focus on just two stories from our practice.

Case Studies for Play

Riverside Park

Our playground at Riverside Park in Guelph exemplifies this thinking. I spent some time at this playground to observe play in action, and to make sure that the spaces we design do what they are supposed to do! As a result, I saw spaces for observing, like the children on the top of this fish sculpture; and spaces for imaginative play, like inside the fish where children were gathering natural materials like hunter-gatherers. I witnessed opportunities for climbing – some very easy and some quite challenging, like on this water strider piece.

With this water strider, I want to pick on the concept of “low physical effort” that’s included in universal design principals. We cannot design with just that idea in mind, because we would not be able to get older kids, or kids who are looking for a challenge, to come outside to play. With this in mind, play spaces must support or offer a full range of effort requirements: from low to high.

When I was at Riverside, I saw that teenagers are not embarrassed to climb. It is great to see them considered in play and be thrilled. One inclusivity tool that we at Earthscape use in our work is variety. Research from Sweden shows that a playground with diverse play spaces can facilitate various ways of processing gender identity. We see that playscapes which have variety of access and egress options – not just ramps – and that have low and high challenges, and opportunities for various types play are, not surprisingly, attractive to a wider variety of kids.

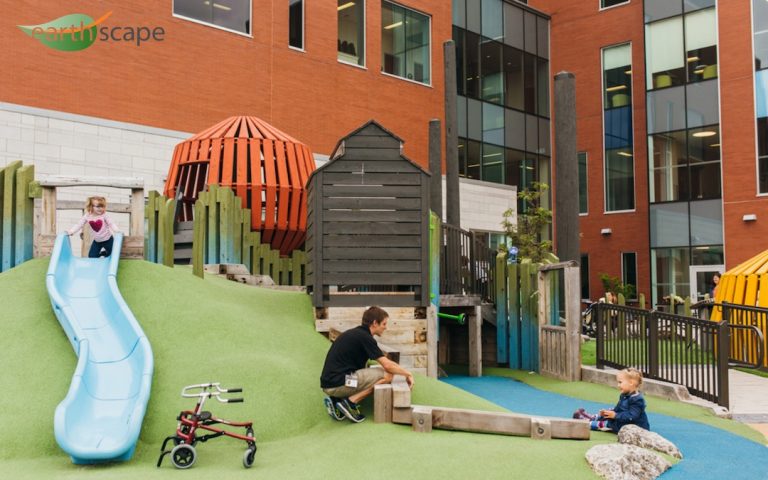

McMaster Children’s Hospital

This photo is from a playground we designed and built at a children’s hospital in Hamilton. It includes several play huts, which you don’t see on playgrounds very much these days. Children with autism-spectrum disorders use these to self-regulate during play, when they perhaps need a moment away from others.

The variety and the combination of open, semi-open and enclosed spaces create a more inclusive overall space. You might criticize this playground as not being inclusive enough. It is a fair criticism – it does not have ramps or movable equipment that can be so great for kids with limited mobility. This is where “variety” meets reality. We build playgrounds not only on set budgets, but strict regulations also dictate a lot of the site layout and the distances between play pieces. Because of this, on a smaller site, some things we get and others we have to give.

I am happy to report that in recent years, we have seen a great shift towards inclusivity from all play manufacturers. As a result, more equipment addresses inclusivity. Designs are considering abilities outside mobility – focusing on different senses: sight, hearing, touch and motion.

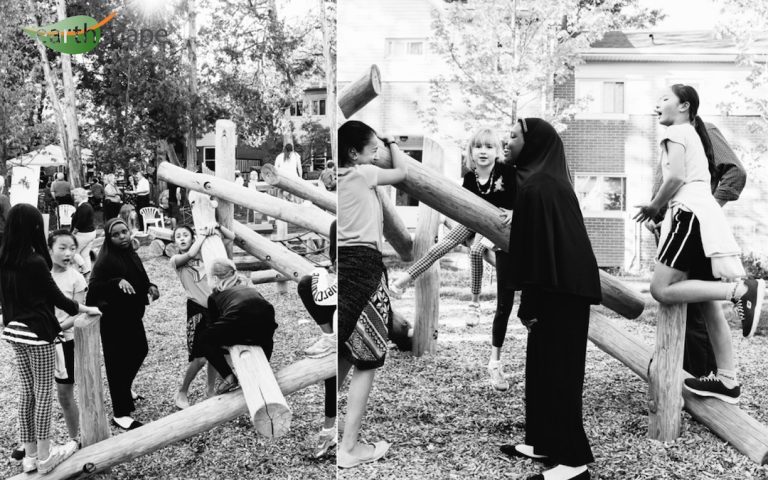

Scissortail Park

This photo is from a playscape in Oklahoma City that we designed and built. As designers, we know so much more NOW about what makes a place more inclusive. Because of this, we now think about ways to create opportunities for interaction and interdependence between peers of different abilities.

Ensuring that spaces are flexible is paramount. As an example, a log jam like this one can be used for kinetic play where bodies move under, over and along logs. But these also create spaces where kids can have conversations in the environments that are exclusively for them.

Final Thoughts

At the start of my presentation, I talked about the interrelationship between good design and inclusive design. I want to leave you with a quote that is attributed to Murri theorist and artist Lilla Watson:

“If you have come to help me, then you are wasting your time. But if you have come because your liberation is bound up with mine, then let us work together” (from Alexis Shotwell’s Against Purity).

Let us work together on the magic of play.

To learn more about events like “The Walrus Talks Inclusion,” visit The Walrus online.